We Need To Think Long And Hard About Flood Insurance

A study shows that providing cheaper flood insurance could make flood damage worse in the future than currently predicted.

As climate change makes extreme weather more frequent and more extreme, policymakers have the overwhelmingly difficult task of designing safety nets for the vulnerable while mitigating climate change. Climate risk assessment is crucial to inform the efforts of policy making. Climate scientists, economists and energy system experts have built a range of scenarios that examine how global society, demographic and political-economy might change over the next century. These are called “Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs)”. There are five such pathways going from SSP 1 to SSP 5.

Future flood risk assessment, for example, is particularly important for regions next to rivers or streams, called floodplains. But the damage caused from flooding depends on the population that is exposed to it. Living next to water has its pros and cons. It is hardly coincidental that property rates tend to be higher the closer you get to water bodies. But as climate change makes flooding more frequent, do we expect people not to change these preferences? Additionally, government policies such as access to flood insurance would also feature into the decision-making of households choosing to settle inland or closer to water.

The problem then becomes a two-way calibration of how population affects flood damage and how the latter affects the former in a dynamic system. But SSPs assume the vulnerability of communities to flood damage to be constant over time.

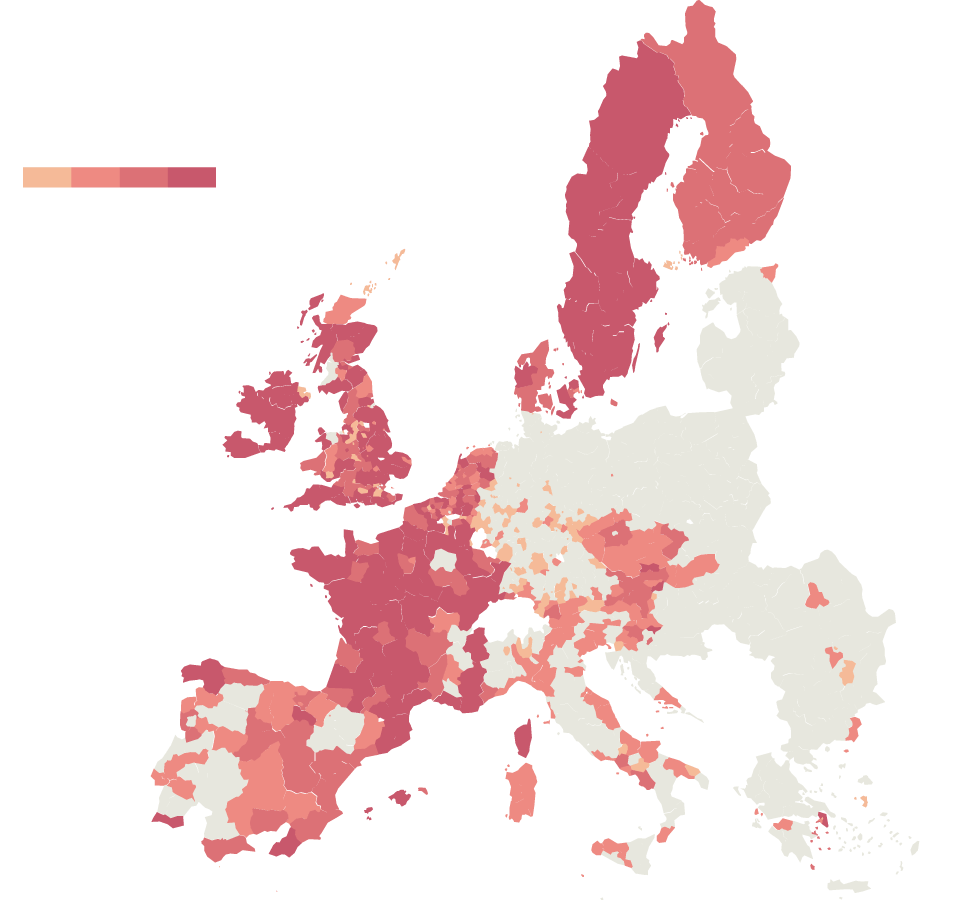

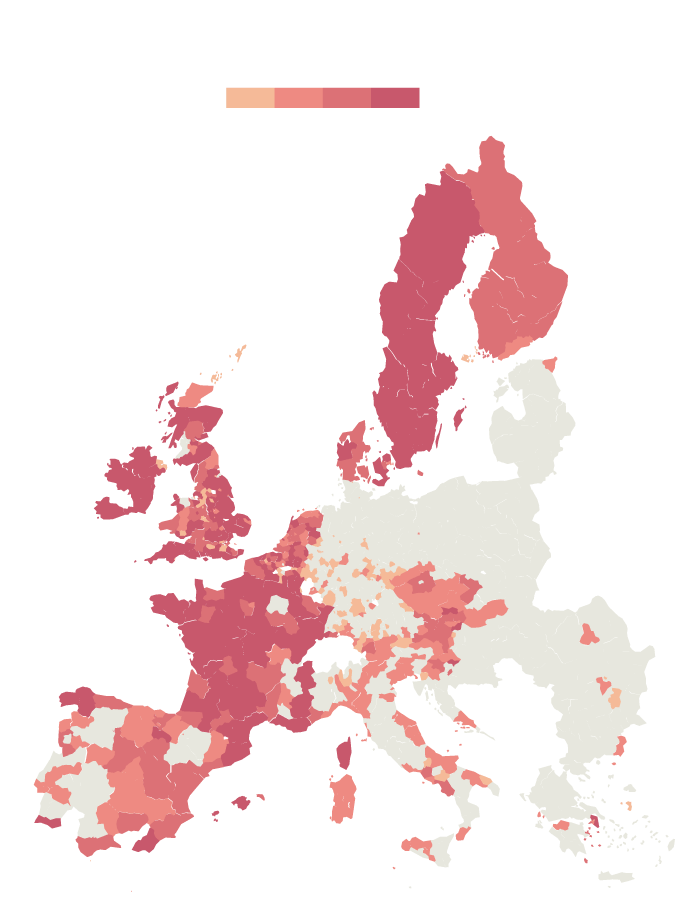

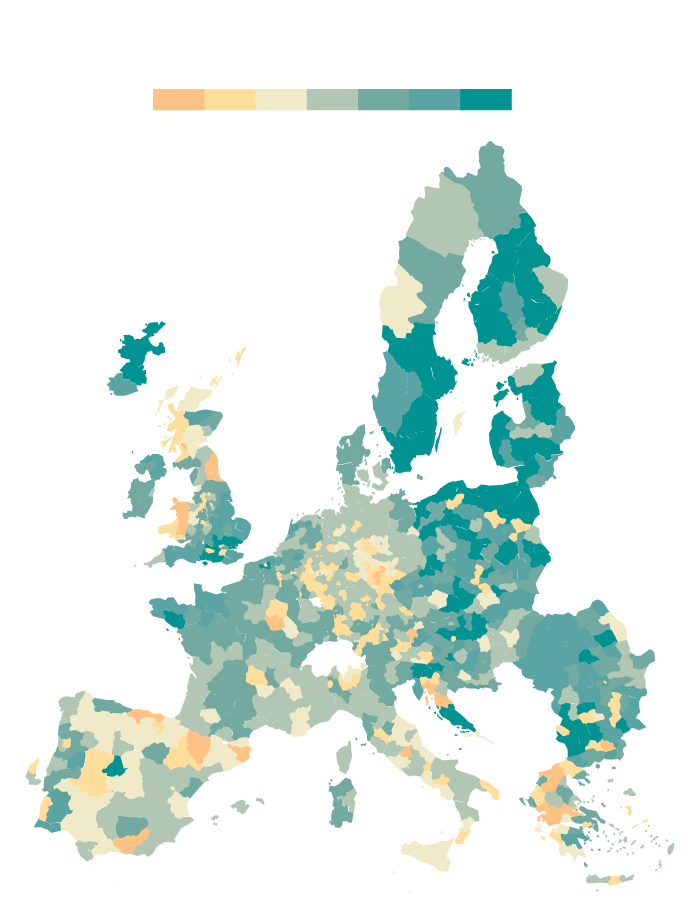

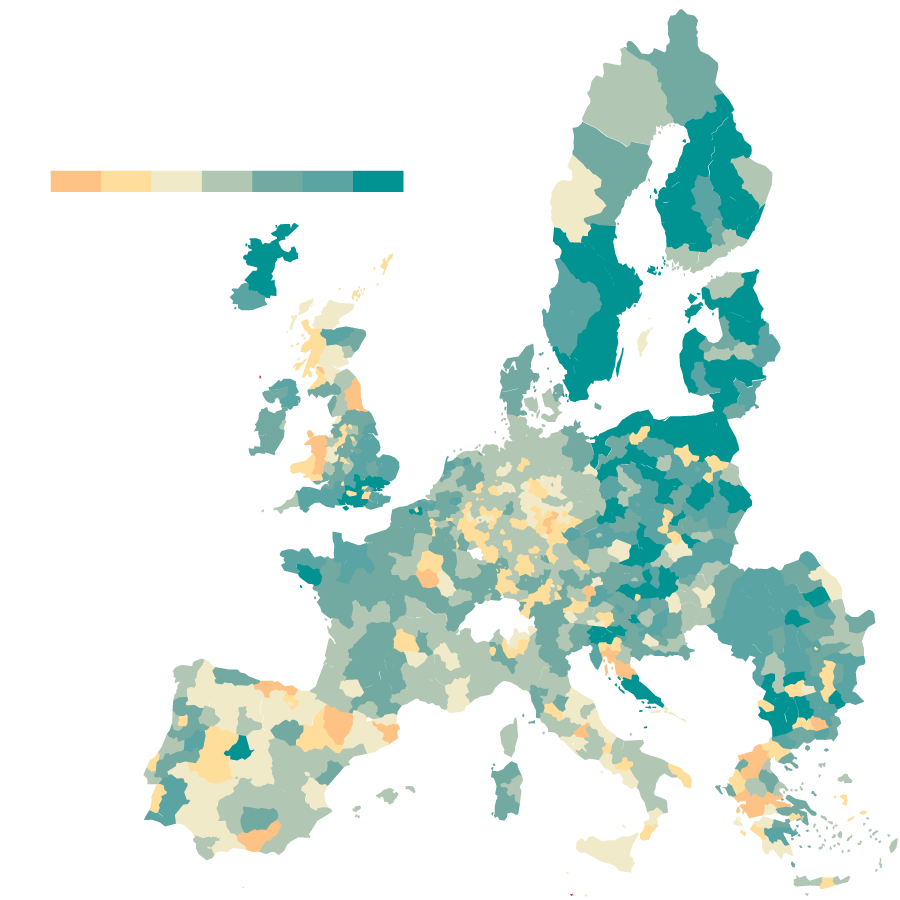

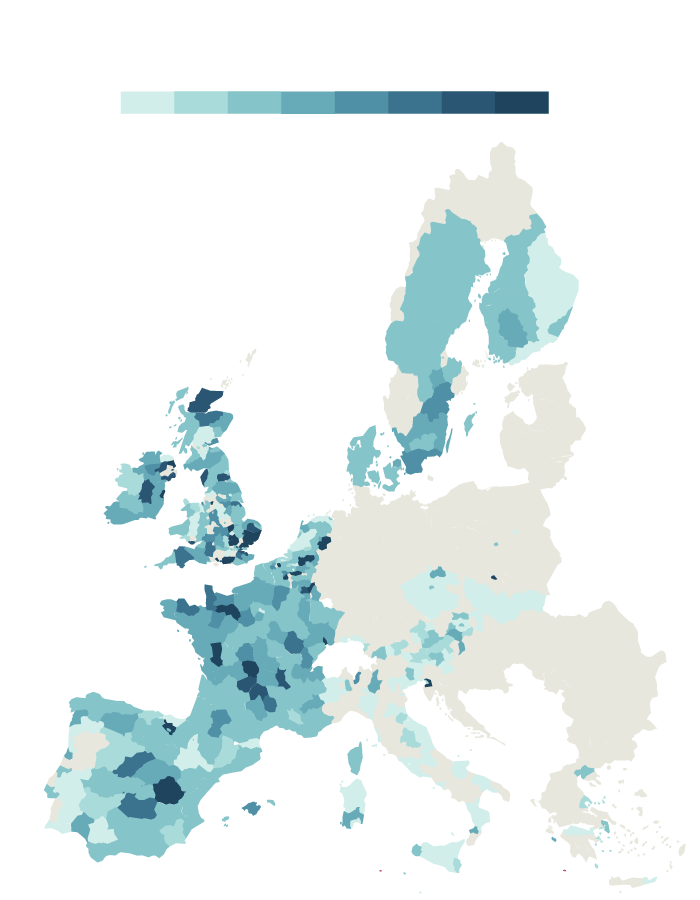

In a study using data from SSP2 (the moderately challenging scenario) on European Floodplains, Max Tesselaar and his colleagues at Institute for Environmental Studies, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam show that population growth in European floodplains and, consequently, rising riverine flood risk are considerably higher in the presence of flood insurance.

"Some studies find that the socioeconomic side plays a potentially greater role than the climatological side in climate risk studies," says Max Tesselaar, explaining that only looking at climate risk scenarios is unlikely to give the full picture of the impact.

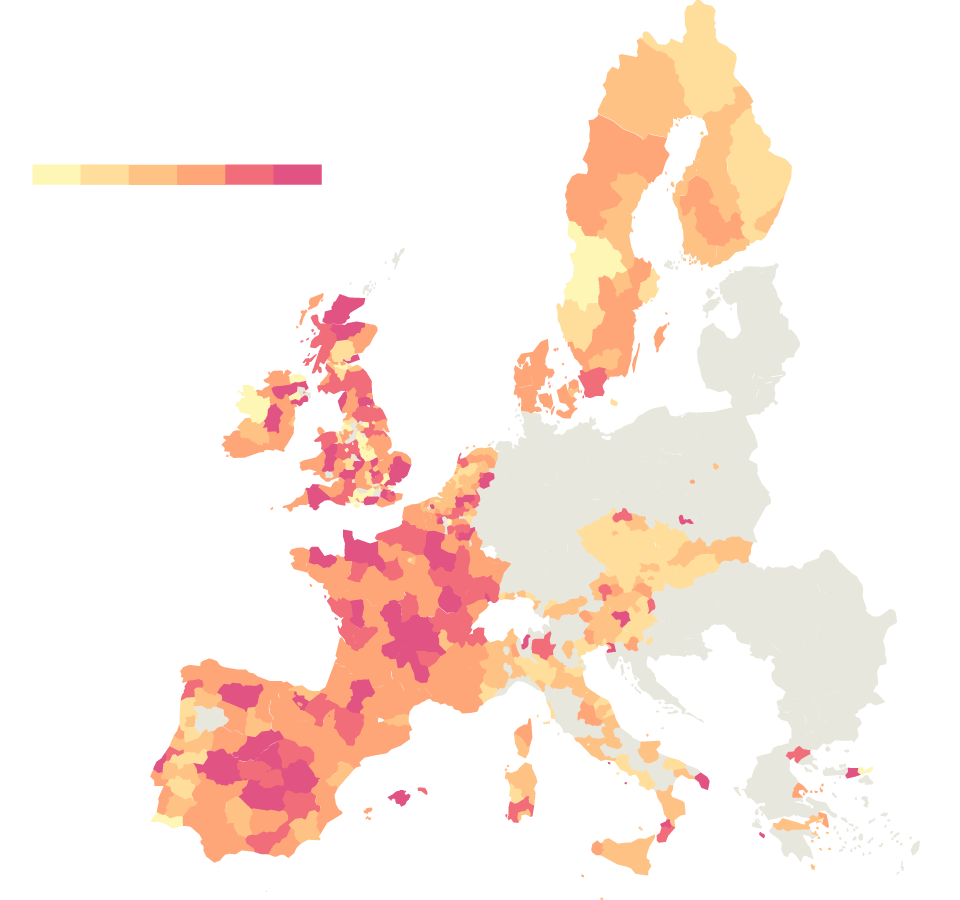

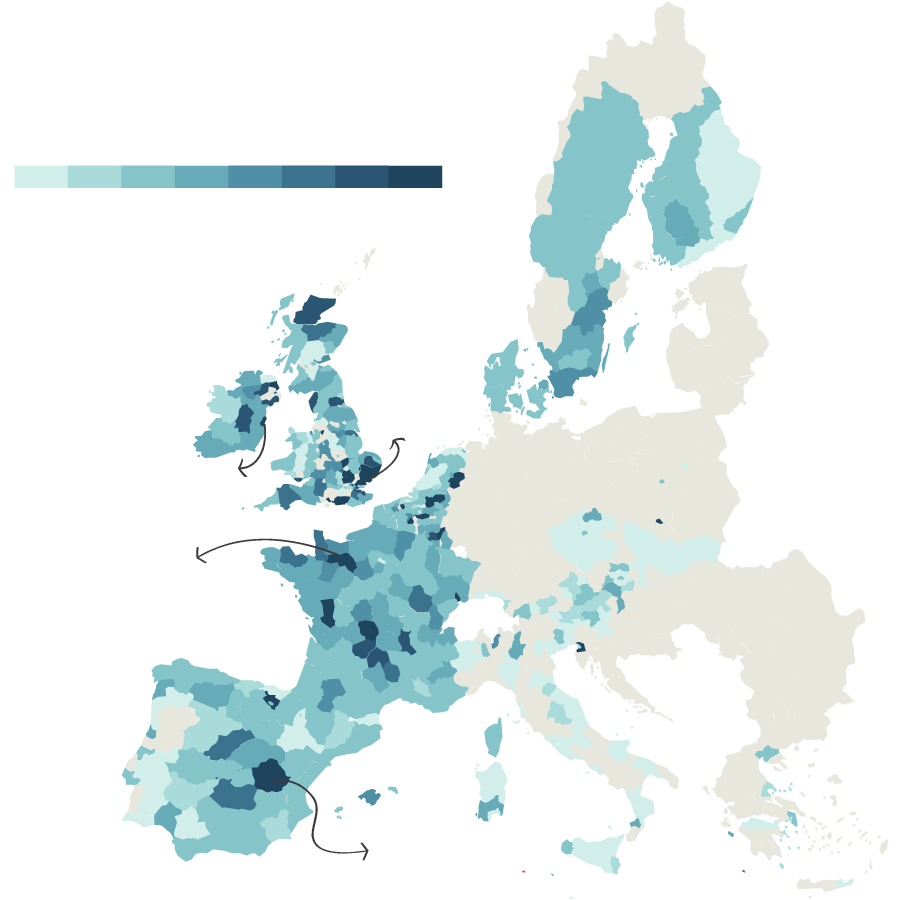

But the type of insurance also makes a difference. In several European countries, including France, Belgium, and Spain national flood insurance policies aim to promote solidarity among households in high- and low-risk areas. This results in something commonly referred to as “risk-pooling” where high and low risk areas end up paying for the ‘average risk’ of the country.

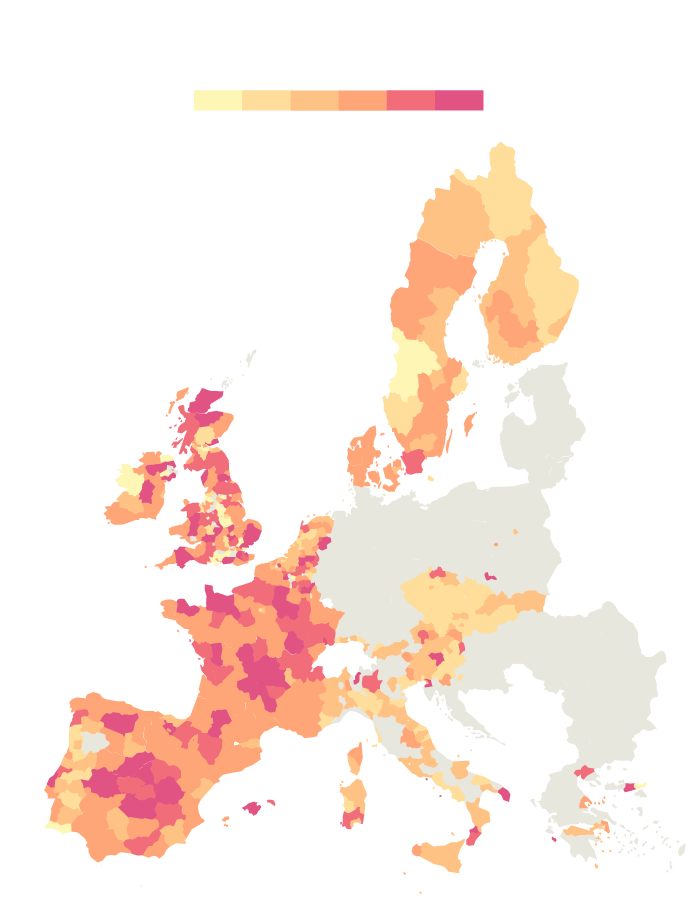

On the contrary, several countries, such as Germany and the UK strive to implement mechanisms that stimulate household-level adaptation, including risk-based premiums. This means that policyholders pay the premium that reflects the risk faced by their property.

Risk-pooling, in effect, passes some of the risk from high-risk properties onto low-risk ones. On the other hand, risk premiums ensure that those who choose to live in more risky areas bear all of the additional cost of this risk. This discourages settlement in more risky regions vis-a-vis the risk pooling situation. The models show that this difference could be significant when it comes to assessing future flood risk.

To measure future flood risk, the authors first measure the impact of insurance on population growth in regions where population is expected to grow. They find that compared to the currently used baseline scenario, the floodplain population growth may be more than twice as high when considering people’s behavioral changes resulting from higher flood risk as well as flood insurance availability.